On Abundance and a World of Silicon Plenty

Just gesturing at a hopeful future isn’t enough to make it so

Close your eyes and imagine a hopeful vision of life just a couple of decades from now: as much leisure time as you want thanks to the use of advanced computers that make the economy hum efficiently and a fridge full of food grown minutes away on technologically advanced farms.

This is what Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson ask readers to see in the opening of their book, Abundance, which has been having a moment. Klein and Thompson argue that we could have a world of abundance rather than one of scarcity, but we’ve simply chosen scarcity.

To wit:

Seen from that future time, when every commodity the human mind could imagine would flow from the industrial horn of plenty in dizzy abundance, this would seem a scanty, shoddy, cramped moment indeed, choked with shadows, redeemed only by what it caused to be created.

Seen from plenty, now would be hard to imagine. It would seem not quite real, an absurd time when, for no apparent reason, human beings went without things easily within the power of humanity to supply and lives did not flower as it was obvious they could.

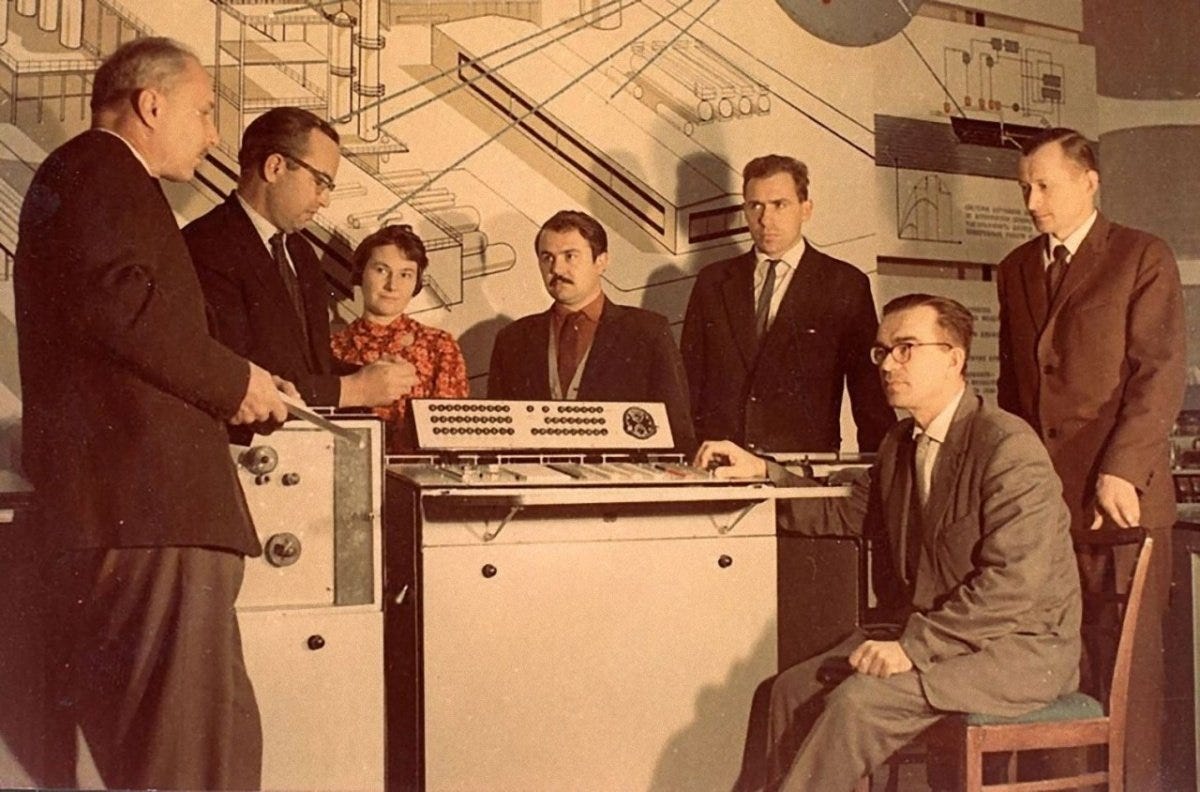

The above is actually not a quote from Abundance, but rather Francis Spufford’s 2010 book Red Plenty, which is a brilliant work about the hopes of the Soviet Union in the 1950s. Red Plenty is about the era under Nikita Khrushchev, when the Soviet Union seemed poised to overtake the United States: they had put Sputnik into orbit and caught up with the U.S. on thermonuclear weapons; the USSR’s economic growth more than doubled that of the U.S., and their “planned economy” was on pace to overtake the capitalist West; their cars, food and houses would soon be better, and there would be more money and leisure all around, thanks to a top-down, start-to-finish management that “could be directed, as capitalism could not, to the fastest, most lavish fulfillment of human needs.”

And all of this plenty would be powered by advances in technology, leveraging algorithms to find efficiencies that would have the nation’s factories and fields gushing forth with an abundance of good things.

If you’ve read Abundance, read commentary on it, or heard any of the dozens of podcasts about it, this will all sound too familiar.

What’s this ‘abundance’ of fuss all about?

Technological innovation is core to the vision in Abundance, with technology serving as a deus ex machina that will make a future of plenty possible — it’s just waiting to be unleashed, but it’s held back by progressive governance. In Klein and Thompson’s view, left-leaning interest groups like environmental activists and unions have become their own worst enemy in achieving progressive goals. The book contends that well-intentioned governance (typically the work of the political left) has created a paralyzing web of regulations, environmental reviews, and procedural requirements that ultimately prevent the construction of housing, clean energy infrastructure, and more. Meanwhile, conservatives have remained too skeptical of the necessity of government involvement in research and development. Both trends result in a lack of innovation that improves healthcare outcomes or quality of life. Their solution involves embracing "supply-side progressivism" that prioritizes building and innovation over regulatory perfectionism, supporting the private sector with government rather than constraining it.

The book has captured the chattering class’s attention because it arrived at a moment of Democratic soul-searching following Trump's reelection. Abundance offers Democrats a way to critique their own governance failures without ceding ground to Republicans on core values; it also offers a way for the Democrats to articulate a hopeful vision of the future rather than simply be the party that has of late not been much more than a clearinghouse for diverse interests who are ‘against’ Trump and Republicans. The idea has particular resonance in California, where as a former resident Klein witnessed firsthand the contradictions of a progressive state unable to build housing or complete infrastructure projects efficiently, and where he was steeped in a culture of techno-optimism, Silicon Valley mythmaking around innovation, and popular corporate mantras around encouraging an “abundance mindset” at work. The book's timing also coincides with continued frustration among younger Democrats facing astronomical housing costs and the abandonment of the party by its former allies in tech, making its optimistic vision of technological and policy solutions especially appealing to those groups.

Abundance focuses on regulatory barriers rather than corporate power and market failures. Klein and Thompson don’t address how how utilities block renewable energy development, for example, or how relying on venture capital investment to produce innovations for public good rather than exploitation has not really gotten the outcomes we want for the last two decades. (Though Klein posted a somewhat defensive op-ed partially addressing some of those points this week). And we've already seen what happens when government provides unconditional support to private actors: it creates figures like Elon Musk, who leveraged public subsidies into personal wealth and political power, or wasteful sideshows like Amazon’s HQ2 contest.

Klein and Thompson's perspective reflects that they are commentariat creatures of the technocratic center-left. The authors appear to be wishing into existence a world where technocrats have expertise that the general public trusts. This world no longer exists, if it ever did. The U.S. cultural baseline is already anti-intellectual and anti-bureaucracy compared to, say, France, Germany, or even the UK or Australia, while the COVID pandemic accelerated public skepticism of institutional competence and elite expertise — a skepticism which, by the way, is something core to the culture of Silicon Valley.

And while union resistance and environmental activism certainly complicate policymaking, it's not at all clear whether process imposed by satisfying multiple stakeholders is always the cause of delays rather than actually a symptom of a lack of political will. Sometimes a project mired in cycles of permitting is indeed obstructed by short-sighted leftist groups, but sometimes those cycles churn as a way of getting broader buy-in where it's otherwise lacking. There's a reason why high-profile luxury housing and corporate capital investment tends to move forward without stalling in permitting stages: the investors in those projects use the political levers available to them to advance their projects with powerful political figures as champions.

Not an abundance of answers to hard questions

I generally believe the theory that candidates and policymakers from either side of the aisle tend to be more successful when they offer a vision of the future — this is the one thing that both Obama’s 2008 campaign and MAGA have shared, and could explain Obama/Trump/Biden/Trump voter — but the devil is in the details. Klein and Thompson offer no thoughts on how the world of Abundance can be brought about with an electorate that’s deeply skeptical of expertise and while both the dominant political players in Washington and dominant culture among technologists is hostile to technocrats.

But they also don’t offer anything beyond an idea for others to do the political work around. The regulations and processes that Abundance agenda advocates dismiss as mere red tape often embody hard-won compromises about environmental justice, worker protections, and democratic participation. Streamlining these away may indeed enable more construction, but it risks recreating the very inequalities and harms that progressive governance originally sought to address and alienating the groups on whose popular support policymakers pushing an abundance agenda will depend. Without a deeper societal trust in technocratic expertise, popular support is all the more important. And if you try to imagine an abundance society without popular support, it will look a lot more like a society with both the dark past and the hopeful future of Red Plenty — fully automated luxury communism, imposed as the happy ending to a period of authoritarianism — which I doubt either a majority of American conservatives or progressives would get behind.

This is where the comparison to Red Plenty begins to be a deeply a useful one. The protagonists of Red Plenty — economists, scientists, computer programmers, industrialists, artists and politicians — all shared the utopian dream of a post-capitalist society in people would be equals and no one would want for anything. There was no debate about what they are trying to achieve; that had already been decided for them by the October Revolution and the Stalinist era that came before.

Corporate power in a land of Silicon Plenty

What is our national project, in the U.S., in 2025? Herein lies the problem. The two major parties certainly don’t agree on much, but they also are rife with internal disagreement on this question. It’s at best a minority view among Republicans that the bounties of innovation and our natural world should be broadly shared.1 And the debate on the left over Abundance appears to be driven by the subtextual argument that the Democratic coalition should abandon some of its more obstructionist members like unions, environmental activists, and those who are skeptical of corporate power if they can’t get on board with delivering an abundant future; those groups will certainly fight hard against that possibility because the Democratic coalition is the only viable pathway to political power they have in the near-term.

But even if right and left can rally around the same version of American utopia, then they will have to deal with the harder challenge of shaping it from the clay of the world we have — and that’s where Klein and Thompson’s techno-optimism and lack of detail fails them, and where Red Plenty offers its best lessons.

By the end of Red Plenty, utopian dreams had decomposed into the realities of the Soviet system. Even though the algorithmic innovation that could make it all work in theory was always just around the corner — perhaps in want of one of the West’s fancy new computer chips — the problem of getting algorithms to fully account for the complex, fluid open systems of the real world remained unsolved.2 Getting accurate demand signals for an economy where goods were produced and distributed without regard for profit margins was impossible. Lacking accurate data3, political leadership in Moscow increased production targets even as equipment became more and more outdated. Pay cuts and scarce commodities led to riots. Ultimately the USSR had to borrow money from the West and import Western grain to feed its population, and still couldn’t keep up with American consumer technology.

Ultimately, the questions Abundance raises are familiar ones of who should have power, and who already has too much. Klein and Thompson see Democratic Party-aligned interest groups as having too much power over our collective future, and some of these groups certainly do create problems out of short-sightedness and self-preservation. But it’s telling that the fiercest debate on the left over Abundance right now is over corporate power and anti-trust enforcement, with Klein and figures like Matt Yglesias arguing that progressives who call out that big companies often behave badly when given free reign are also part of the problem.

Yglesias has an outdated conception of the problem that corporate power and monopolization creates: that corporate power is a problem when companies use that power to artificially raise prices to a point that’s a detriment to consumers. Meanwhile, Klein admits corporate power *can* be a problem but believes that Democratic messaging on it is a distraction.

Klein is correct that the anti-corporate left is unfocused (though he doesn’t say what they should focus on), and Yglesias is correct that competition law was originally meant to address vertically-integrated businesses with monopolies on pricing like Standard Oil, not a business that doesn’t charge its users anything like Meta (and as a consequence he fails to see that corporate size can create other problems beyond just prices). Both miss the bigger point that we face a choice on who we trust to wield power in bringing a utopia of abundance into being — technocrats, activists and interest groups, or corporations. Klein and Yglesias are seemingly both choosing to vest that power in the technocrats, even though there is currently no viable political pathway to that, and even though that path will likely end up further empowering the corporations.

We do live in a world of finite resources, and so long as a powerful, unaccountable few are directing the distribution of those resources in such a way that does not serve the goal of everyone existing in a world of plenty, we will have scarcity. That’s a thesis from Abundance that I can agree with.4 But failing to account for the fact that so much of our lives — what we buy, how we buy it, why we buy it, what culture we consume, what we think about politics, and even the future of our economic livelihoods — is shaped by a handful of unaccountable companies that wield incredible, increasing political power will ensure Abundance remains but a dream.

Perhaps the greatest irony of Abundance’s vision of Silicon Plenty is this: catering to short-term consumer gratification is ultimately what killed the Soviet vision of innovation and abundance; and today we are promised a similar utopia is around the corner, but it depends on giving free reign to a handful of businesses that have become the biggest corporations in history by catering to short-term consumer gratification.

We can expect “abundance” arguments to be widely used on the right, in large part due to the lobbying of the tech industry will use these arguments. American tech companies have long benefited from the assumption — usually unquestioned by the right — that continued American dominance depends in turn on the dominance and unaccountability of a handful of American tech businesses. This is how tech companies have been successful at leveraging the “we must keep ahead of China” argument to kill attempts to rein them in, most recently with the proposed moratorium on state AI laws.

That this is eerily similar to the shortcomings with large language models failing to understand the physical world is not, in my view, a coincidence.

Arguably the Soviet state lacked good quantitative data because of the price signal issue but also lacked qualitative data because that’s inherently hard to gather. We struggle at this in 2025 in the United States, too in my opinion. Silicon Valley and our largest tech companies are very good at extracting lots and lots of data on us, that data is used to paint a picture of “what can we be convinced to buy” rather than “what do we need to thrive” because of their incentives to maximize revenue.

Having lived for a time in a post-Soviet society as a Peace Corps volunteer in Moldova, I can say with confidence that I don’t want to live in a world where such power is vested in an unaccountable, authoritarian government. But vesting that power in executives like Mark Zuckerberg or Sam Altman or Marc Andreesen also doesn’t seem much better.

'the problem of getting algorithms to fully account for the complex, fluid open systems of the real world remained unsolved.'...'That this is eerily similar to the shortcomings with large language models failing to understand the physical world is not, in my view, a coincidence.' A masterpiece of judicious understatement. Of course people who can't deal with even the messiness and ambiguity of normal human society will want to replace it with a digital simulacrum that can be controlled, tweaked - and switched off - at will. Thank you.

'the problem of getting algorithms to fully account for the complex, fluid open systems of the real world remained unsolved.'...'That this is eerily similar to the shortcomings with large language models failing to understand the physical world is not, in my view, a coincidence.' A masterpiece of judicious understatement. Of course people who can't deal with even the messiness and ambiguity of normal human society will want to replace it with a digital simulacrum that can be controlled, tweaked - and switched off - at will. Thank you.