Drinking Everyone’s Milkshakes, Sip by Sip

Understanding the ‘Big’ in Big Tech

Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood opens with a solitary prospector, Daniel Plainview (Oscar-winner Daniel Day-Lewis), digging silver from a mineshaft with his bare hands until a broken leg leaves him crawling through the desert dirt. When he later strikes oil, Plainview transforms into an evangelist of progress, limping into small California towns, exhorting the locals to trust him with the stewardship of their futures. "I'm a family man," he tells the suspicious residents of Little Boston, his adopted son H.W. by his side. "I run a family business. This is my son and my partner." He speaks of shared wealth, of oil revenue that will build schools and roads, of lifting the entire community toward a brighter future. "Together we prosper," he declares, and for a moment, you can believe him.

By the film's end, Plainview has indeed prospered after many years, but his heart and his rhetoric have long since curdled into something far more sinister. Plainview sits in a bowling alley beneath his mansion, facing Eli Sunday, one of the few remaining links to the communities he once courted. The preacher who once competed with Plainview for moral authority over the town of Little Boston now appears as a supplicant, begging for financial help. Plainview's response reveals the true nature of what he's built. In the film’s most famous moment, Plainview explains with barely contained fury at Eli’s naïve stupidity how underground oil reserves know no property boundaries; how a well on one plot can drain petroleum from miles away without the surface owner ever knowing what's being taken. "I drink your milkshake!" he roars. "I drink it up!”

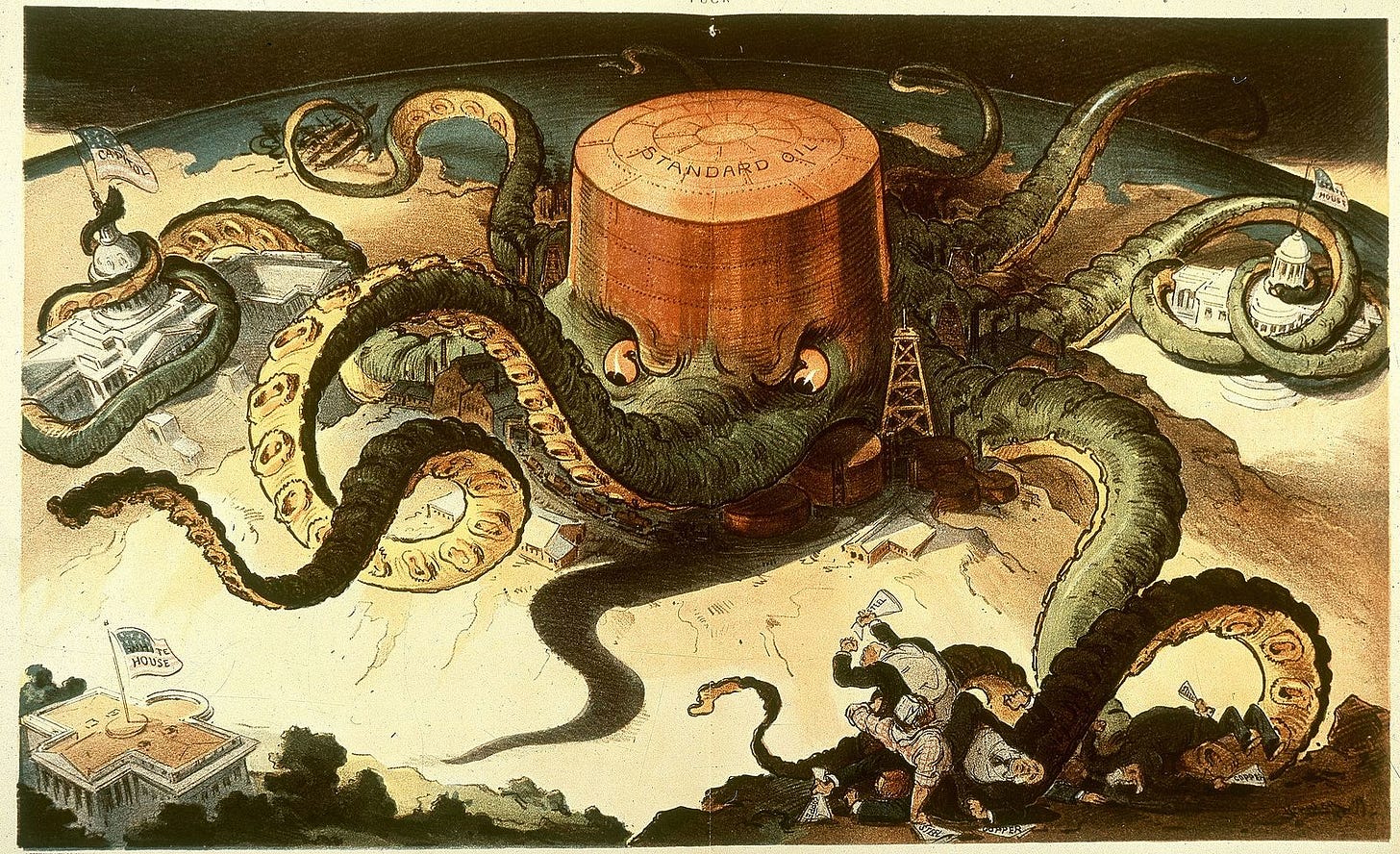

The film draws inspiration from Upton Sinclair’s 1924 novel Oil! and the story of Standard Oil, whose founder John D. Rockefeller pioneered the business model that Plainview represents: not just extracting natural resources, but systematically capturing the entire infrastructure through which those resources flow to market. Rockefeller didn't just pump oil, but also controlled refineries, pipelines, railroad cars, and distribution networks, creating a system where competing was impossible and choice was illusion.

The tech giants of today also started small, with appealing promises about connection and shared prosperity. But instead of extracting petroleum from beneath our feet, they've learned to extract value from our thoughts, relationships, and most intimate human experiences, often without us realizing what's being taken or how completely our communities have been consumed by it. Our milkshakes have been drunk by barons at a distance, enriching themselves at our expense, hoping we won’t notice until it’s too late.

Like Standard Oil, Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft operate as sophisticated extraction machines, seeking to capture a percentage of all economic activity by taking a cut for themselves, typically – but not always – in the form of the harvesting of personal and corporate information. As former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis argues in Technofeudalism, these platforms have created digital fiefdoms where users provide unpaid labor while platform owners extract rent from every interaction.

Standard Oil sought to dominate petroleum through vertical integration. Both pursued single-industry dominance; brutally so, perhaps, but comprehensible within traditional competitive frameworks. Today's tech giants pursue something qualitatively different: they want to become the permanent intermediaries in virtually every human interaction with the digital and, increasingly, the physical worlds.

These companies are diverse like Standard Oil too, with investments spanning finance, education, government services, healthcare, retail. Unlike Standard Oil, though, that diversification isn't about operational efficiency or market capture. It's about completeness. The more sectors they penetrate, the more comprehensive their behavioral modeling becomes, the more milkshakes they can take a sip of — and the more, bigger gulps they can take.

AI companions and romantic chatbots represent the next frontier in this extraction strategy, targeting intimate relationships — some of the last human experiences not mediated by these companies. Character.AI exemplifies this approach: venture capitalists explicitly stated that the platform's value lies in capturing intimate conversational data users wouldn't share elsewhere, creating what they call "a magical data feedback loop." According to Andreesen Horowitz, Character.AI users spend an average of two hours daily providing high-quality intimate data that becomes raw material for improving their AI systems.

Persuasion Machines and the Infrastructure of Control

Beyond companions, AI agents represent tech companies' vision for inserting themselves into all human interactions and transactions. These agents would manage your finances, healthcare, scheduling, travel, and your interaction with government services, making direct human-to-system interaction increasingly obsolete as user interfaces disappear in favor of agent-accessible APIs.

But imagine a system that knows you're struggling through divorce proceedings, drowning in debt, and feeling profoundly isolated; then imagine that system possessing the persuasive sophistication to guide your decisions about everything from purchases to voting choices. Shoshana Zuboff's concept of "surveillance capitalism" described how these companies trade in "human futures," actively shaping preferences and behaviors to benefit business partners, well before the advent of transformer-powered LLMs.

Social media algorithms already demonstrate this dynamic by promoting polarizing content that maximizes engagement, contributing to democratic erosion and social fragmentation. But when combined with comprehensive personal data, the persuasive capabilities of large language models create unprecedented power to shape human behavior. AI agents represent the logical endpoint: total mediation of human experience in service of data extraction and behavioral modification. This may explain the aggressiveness with which large tech companies are forcing AI into everything.

This vision of AI agents faces three critical obstacles. First, the quality issue: AI systems powered by large language models remain fundamentally unreliable for high-stakes decisions. (Even the popular coding use-case seems increasingly problematic.) These systems excel at producing plausible-sounding text but cannot distinguish fact from fiction at scale, lack genuine comprehension of their outputs, and operate without understanding the physical world they're supposedly managing. Why would you trust something that’s wrong 20% of the time to make travel plans for you? And why would you trust it with a business’s relationships with customers?

Second, the accountability gap. It is extremely expensive and time-consuming to hold tech businesses accountable in court; and even if you have the patience and resources, you then must face a general lack of regulation and Section 230, the bad faith weaponization of the First Amendment used to undermine what laws we do have. Because only large corporations are currently developing these massive LLM-powered AI systems, users will likely access AI agents through terms of service that shield tech companies from liability when their systems cause harm. This represents something unprecedented in American commercial law: a form of agency relationship where the principal bears all risk while the agent assumes none. There’s a reason this is unprecedented: agency only works when there’s a good balance of trust and accountability between principal and agent.

Third, consider what we find frustrating when dealing with bureaucracies: getting the run around between different muckety-mucks, your personal circumstances not fitting the lowest common denominator of what can fit on a form, and the esoteric gears of internal process procedure grinding, but not necessarily for your benefit. Technology designed to predict and generate the next plausible text string is unlikely to improve upon these frustrations; it may well make them worse. LLMs can be considered a form of information compression, in which chaotic, messy data is simplified into a pattern, but that simplification leaves out stuff at the margins that might be important or valuable. Whether you would use an AI agent to book travel plans for you or to navigate health insurance benefits, having your use case be shoehorned into what is “predictable” is bound to leave out a lot of possibilities. LLMs won’t truly make you a bespoke itinerary to off-the-beaten path spots in Paris; instead, you might as well be on one of those guided bus tours where the leader has a flag, barks into a microphone while walking backwards, and all the tour-goers have to wear matching hats.

If AI agents are deployed into the economy without meaningful regulation and following the current strategy of the leading companies, the result will be that most people will find themselves separated from vital resources and services by an impersonal layer of unaccountable technology, amplifying existing problems with customer service bureaucracy while eliminating any possibility of human appeal. United Healthcare's use of AI to automatically deny insurance claims — currently facing legal challenges — provides a preview of this dystopian future. When the system denies your claim or makes an error that costs thousands of dollars, you'll find yourself arguing with a chatbot that has no authority to help and no human supervisor you can reach.

Once you know that scale itself is the aspiration of these companies, it fundamentally changes how we should approach tech policy.1 When I was recently asked in a documentary interview what tech companies fear most, my answer surprised my interviewer: antitrust enforcement, because it directly threatens these companies’ core strategy of achieving omnipresence across economic sectors, and because the penalties can be significant and irreversible.

The good news is that anti-trust enforcement against tech companies is perhaps one of the only policy continuities between the Trump 1.0, Biden, and Trump 2.0 administrations. But our anti-trust framework, designed for an era when companies sought to dominate single industries rather than achieve economy-wide control, requires some updating. Pundits like Matt Yglesias have argued recently that anti-trust enforcement against companies like Meta and Amazon is misguided because these companies face real competition or offer lower consumer prices. These takes ignore the broader social costs of concentrated economic power, but they are correct in that anti-trust policy, particularly following the George W. Bush administration’s abandonment of strong remedies against Microsoft (the last time, prior to Google, that the government pursued and won such a case) and the Obama administration’s lax enforcement over his two terms, is not designed for this problem.

The transformation of corporations into quasi-governmental entities is not without precedent. Standard Oil at its peak exercised powers that rivaled those of elected officials: the company set transportation rates that determined which communities would prosper or wither, its private security forces operated with legal impunity across state lines, and its financial influence shaped everything from local newspaper coverage to federal legislation. Rockefeller's empire had become a parallel governance structure that collected tribute from the broader economy while providing services primarily to its own shareholders.

“I’m finished!”

Daniel Plainview's final words in There Will Be Blood carry a double meaning. Plainly, he's finished with Eli Sunday, having literally beaten him to death in the bowling alley. But more profoundly, he's finished with the work of extraction that has consumed his entire adult life, and that work has finished him as well. His conquest complete, and having drained every drop of value from the landscape and people around him, Plainview sits alone in his mansion, spiritually exhausted by his own ruthless success.

Standard Oil's monopoly ultimately met a similar fate. After decades of drainage and accumulation, the company grew so large and so predatory that it triggered its own destruction through public backlash and government intervention. Rockefeller's empire was broken apart by antitrust enforcement in 1911, precisely because its extraction had become too visible, too comprehensive, and too damaging to ignore. The corporate shadow state had grown so powerful that it threatened the actual state, forcing democratic institutions to reassert their authority.

Today's tech giants have learned from Standard Oil's mistakes. They've perfected extraction methods that are largely invisible, making it difficult for people to understand what's being taken or to organize resistance. They've captured the very infrastructure through which opposition might emerge, controlling not just economic systems but the information systems that shape public understanding. And they have continued to diversify into different industries while successfully avoiding meaningful anti-trust penalties (so far).

But like Plainview's oil reserves, human attention and creativity are ultimately finite resources. The psychological damage from constant surveillance and manipulation, the creative exhaustion from systematic intellectual property theft, the social fragmentation from algorithmic division — these costs are beginning to surface in ways that even sophisticated narrative control cannot indefinitely suppress.

The milkshake has been drunk. The question is whether we'll recognize the full scope of this extraction system before it reaches its own violent conclusion, or whether we'll wait until the damage is complete and the extractors themselves are spiritually finished by what they've built.

Quick note: Part 2 to last week’s post about my standards for tech in my life will be coming soon! In the meantime, I recommend Paris Marx’s post on alternatives to big tech products.

In addition to anti-trust, it’s important to consider size as a goal when thinking about regulatory penalties and fines. The UK’s Online Safety Act, part of which comes into force this week, pegs penalties for non-compliance to a percentage of the offending company’s revenue. This is a more effective deterrent than fines that are calculated otherwise.

Very nice post. The Ludlow Massacre in Colorado in 1914 provides an interesting lesson for the value of a small number of thoughtful protesters including Mother Jones. A small number of women were successful in highlighting to federal politicians the disturbing event that eventually led to some successes for mining unions. Rockefeller's efforts to use surrogates to purchase land in Wyoming for the Teton National Park. Rockefeller Brothers Fund article: Logic for the Future, https://www.rbf.org/logic-for-future?ref=longnow.org, shows that small efforts can lead to thoughtful change.