A Field Guide to AGI Hype

Whose opinions on AI should you question — and why you should care even if you normally avoid AI in the news

If you’ve somehow have made it the last 18 months without hearing the terms AGI — “artificial general intelligence” — or even ASI — “artificial superintelligence” — then please accept my congratulations.

But of late, the numbers of the blissfuly unaware are shrinking. Since claims about how to even define AGI vary wildly (look for a future post about this), much less how we will know when we will “reach AGI”, I’ve noticed growing confusion in the general public about whose perspective to trust.

This has been worsened by the fact that trusted, non-tech sources for political and social commentary — people like Ezra Klein, just to name a person whose work I typically appreciate but who I will pick on throughout this piece when it comes to AI — have also given platforms to people making big claims about AI in the recent past, sometimes repeatedly, and in my opinion have tended to not ask a lot of difficult questions of their interviewees, instead taking claims about AGI at face value. There’s also labels thrown about, like AI doomers and techno-optimists and AI skeptics, but apart from the AI “accelerationists”, few people self-describe themselves as a doomer or skeptic, so it’s hard to know where people stand and how to apply critical thought to their AGI claims.

I’ve put together a taxonomy that can help you understand why some people make the claims they make about AGI, decide for yourself who to trust, and begin to know how to interrogate claims.

Even if you avoid AI clickbait or otherwise don’t care (as I’m aware that many of you found me from my post on After Babel, and thus may be more interested in social media or kids online safety), this has relevance for you. Not only does AGI hype often benefit companies like Meta and Google economically, but increasingly wild claims about AGI are being used to halt progress on making much needed policies to protect kids online and reform the tech industry.

And so, without further ado, here is the taxonomy:

Those with a strong economic or professional investment in AGI

Those with a social or minor investment in AGI

Those who spiritually yearn for AGI

Those who find AGI useful politically

1. Those with a strong economic or professional investment in AGI

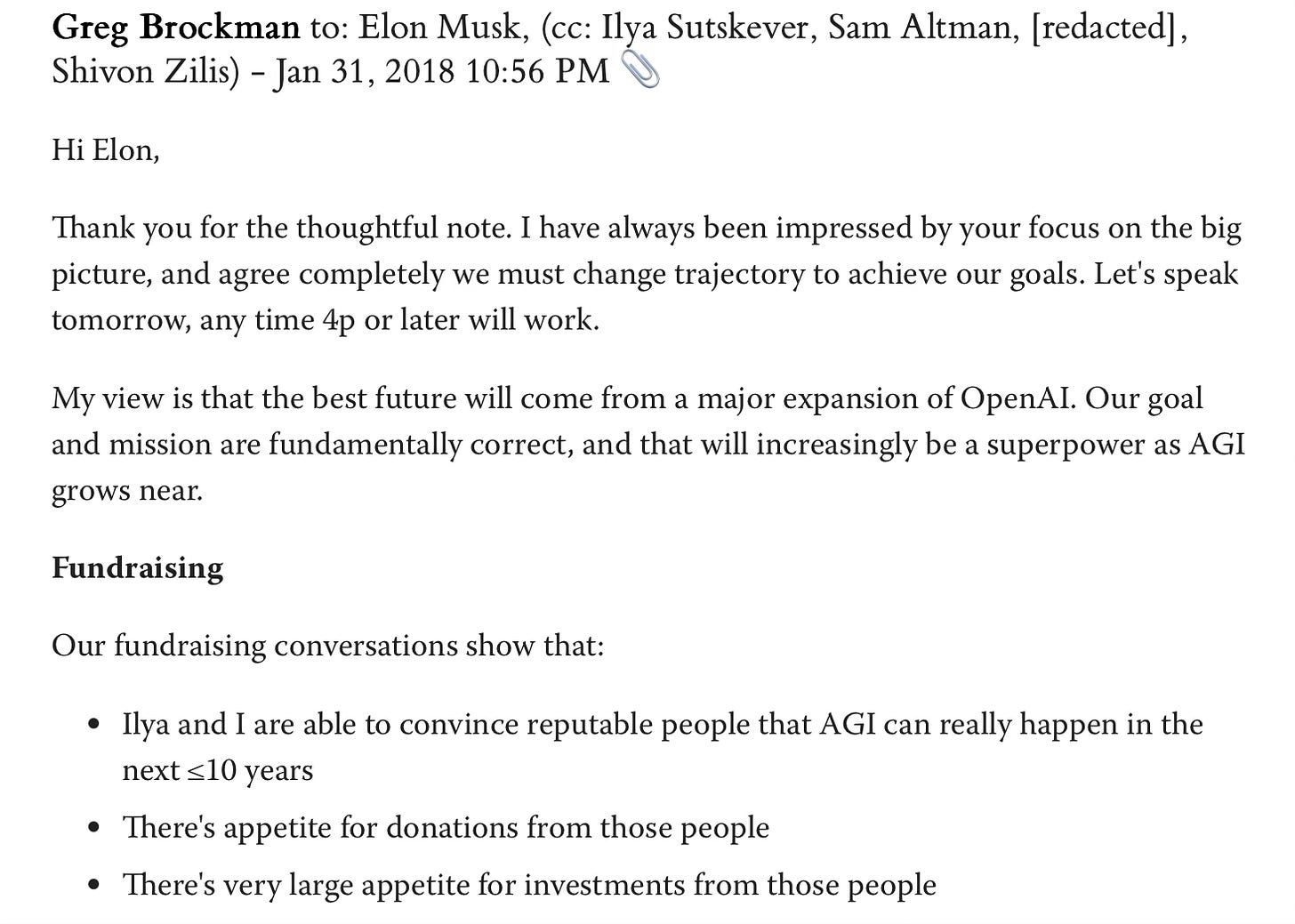

Sam Altman of OpenAI and Dario Amodei of Anthropic are two of the most obvious examples here, but this also applies to companies like Meta and Google: they and their products may well not merit the investment and cheap energy and water they need to keep their money-losing AI businesses going if they can’t convince investors and governments that they are building something more powerful than ChatGPT or Claude or Google Gemini. We actually have the receipts for this from OpenAI, from an email disclosed in litigation in which Greg Brockman, current president of the company, explicitly made a connection between getting potential investors to believe in AGI and actually receiving funding:

Once you’ve seen this email, it’s harder to un-see the incentives of some of the hucksters out there. Ilya Sutskever, also formerly of OpenAI and on this same email chain above, has started a new company, for which he has already raised at least $2 billion in funding based only on his claim that he’s building artificial superintelligence. He won’t disclose his methodology, and there doesn’t even seem to be a business plan for monetizing any technology he does produce. That’s right: investors have given him a $30B valuation to fund development of a purely theoretical technology, for which there is no existing design or prototype, and which were it to become real, could fundamentally remake the worldwide economy overnight. But he evidently has no plan for how to make money from it or for investors to recoup their investment. (Not to mention, if we create a superintelligence that’s truly beneficial for humanity, will we even need money or investors anymore?) Talking about AGI is really all that Sutskever has to go on.

But there’s also more nuance here too. “Godfathers of AI” like Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshua Bengio, have appeared more and more in the news over the last two years,often making grand claims about how we are close to the event horizon of AGI. These are certainly brilliant men who are much smarter than me,1 and I want to be clear that I am not impugning their conscious intentions. But it’s a reality they also would not be as relevant, with the opportunities for funding and exposure that they currently receive, if they were only claiming that the LLMs we have will eventually amount to normal technology that we otherwise fit into the economy and society. The grander the AI, the more important these men and their work becomes. I would personally be less skeptical of them if they made more of an effort to use their status to combat present-day issues with technology; in my experience their engagement with lawmakers has served to undermine much-needed policy changes; see, e.g., the three experts’ support for last year’s California Senate Bill 1047, which created the very foreseeable blowback of the state AI moratorium proposal I wrote about last week.

This analysis, unfortunately, also applies to nonprofits and public-interest oriented startups working in the space. First, a nontrivial amount of deep-pocketed non-profit donors interested in AI issues have strong beliefs about AGI, and so it pays to cater to them. Second, some wealthy engineers have started AGI alignment start-ups or nonprofits (the former usually requires other investors to scale, the latter requires diverse funding to qualify for 501c3 status so as to not just be a private tax benefit for the founder), and they have an incentive to promote AGI narratives to justify their organizations’ existence and reach the aforementioned donors/investors.

2. Those with a social or minor economic investment in AGI

I also have a general sense that AGI has become a raison d’etre for shallow social connections in the Bay area. On my visits to SF I can’t help but feel that many people in tech struggle to make life-long friendships, and perhaps this is the result of an engineering culture that thinks that things like friend-making can be optimized.

Just like it’s hard to imagine what Minnesotans would talk about if they didn’t have the weather, I’ve been in enough rooms with enough Bay-area tech elites to wonder what they would talk about if they didn’t have AGI. Not everyone is SF is working on AGI, but everyone seems to have friends who are, and why wouldn’t you want to agree with the experts in your social network so that you can continue to belong? I have had the experience of personally suffering through social pressure to hype AGI by those with an incentive to push it (see above), and frankly, I’ve seen that it has an impact on others who you’d otherwise expect to know better. If you want to fit in at Burning Man, you better be ready to talk about your AGI timeline and your p(doom).

I think the social element in part explains why someone like Ezra Klein has, to date, been a mouthpiece for claims about AGI. He relocated to San Francisco years ago, (though now is in New York), and I am aware that he runs in the same social circles as many of the figures promoting AGI (I’m, at best, like 3 degrees of Kevin Bacon socially removed from him, but people talk). Klein’s clearly interested in AGI because his social circle is interested in it, and if you want a shot at getting on his show, you better be interested in it too.

But this dynamic also extends beyond the Bay area crowd. For example, Eric Schmidt, former Google CEO and coauthor of a recent book on AI with Henry Kissinger, is probably perceived as a more serious person than, say, Sam Altman is, and is close with serious people like former President Obama. Schmidt, who still owns around 1% of outstanding shares in Google parent Alphabet, certainly has a financial incentive to promote AGI hype. If you’re a busy but serious person, and Eric Schmidt is telling you AGI is imminent, why not repeat what he told you instead of digging into it yourself?

3. Those who spiritually yearn for AGI

If you've been following AI for a while, you've likely have noticed a striking overlap: the Venn diagram between Effective Altruists (EAs) and those making the most dramatic claims about AGI is nearly a circle. This isn't coincidental – for many in the EA movement, AGI represents nothing less than a technological messiah or potentially a technological anti-Christ. It could go very, very wrong in their view, but if we get it right, it can usher in a new era for humanity thriving.

If you aren’t familiar with it, the EA community operates on a morally dubious calculus where hypothetical future lives trump real present suffering, on the justification that there are going to be many more millions of lives in the future than there are today. They've convinced themselves that optimizing for "the most good" means prioritizing statistical fantasies of trillions of hypothetical people over addressing tangible harms happening right now, and they believe they can quantify human flourishing down to utilitarian decimals. Many AGI groups’ funding networks trace back to EA-aligned tech billionaires like Dustin Moskovitz and the now-disgraced Sam Bankman-Fried.

Why AGI? Because it provides the ultimate escape hatch from messy, present-day moral obligations. If you believe you're working on an intelligence that will either solve all problems or end humanity, suddenly climate change, inequality, and other current crises become mere footnotes. You're not just avoiding difficult present-day ethical challenges; you're reframing your moral abdication as virtue. The Excel-spreadsheet approach to ethics – where "doing good" becomes a maximization problem rather than a human obligation – finds its perfect expression in AGI discourse.

Eliezer Yudkowsky might seem to have a different, oppositional perspective, but it serves the same psychological function. His followers find profound purpose in believing they're working to prevent the apocalypse, a calling that borders on religious devotion. We've seen this pattern before with apocalyptic cults: the threat of imminent doom provides meaning and community cohesion. It's harder to get exercised about addressing present-day algorithmic harms when you believe superintelligence will either solve everything or kill us all within a decade.

The rational veneer of AI discourse often masks what is, at its core, a religious movement complete with its own prophets and sacred texts (usually internet newsletters or manifestos like Scott Alexander’s and Daniel Kokotaljo’s recent AI 2027 document).

When someone tells you AGI is three years away, it's worth considering whether the similarity between these claims and the Heaven's Gate cult from the 1990s or those who believed that Mayan codices predicted the end of the world in 2012 is merely superficial. In each case, we see the same pattern: a technological or cosmic event of world-changing significance, always just over the horizon; a self-selecting group of enlightened believers who alone grasp the true nature of what's coming; and a conviction that preparing for this imminent transformation is the most important work anyone could be doing. The only real difference is that our modern technological prophets often have venture capitalists backing them, and perhaps more importantly they don’t seem willing to die for their beliefs — so far, anyway.

4. Those for whom AGI is useful politically

AGI narratives serve a dual purpose in political discourse: they simultaneously deflect attention from present-day harms while setting the stage for regulatory frameworks that favor established players. Tech leaders like Sam Altman strategically pivot conversations about data piracy or deepfake pornography toward speculative futures where superintelligent systems solve all our problems – effectively distracting from accountability for current technology's social costs. Meanwhile, ostensibly well-intentioned AI safety groups advocate for regulatory regimes that would create complex compliance frameworks that box out smaller players, without addressing the underlying lack of accountability for bigger tech companies in the system. The political utility of AGI talk thus spans from outright distraction to sophisticated maneuvering for market advantage, all while wrapping these moves in either techno-utopianism or safety concerns.

But for politicians themselves, the AGI narrative serves distinct political purposes across the ideological spectrum, becoming a convenient vehicle for radically different visions of social reorganization.

Followers of Dark Enlightenment figures like Curtis Yarvin see AGI as a handmaiden to a form of desirable (for him) corporate authoritarianism. For this crowd, AGI represents the perfect instrument for their "CEO of America” fantasies, a hyper-intelligent advisor to the enlightened dictator who will finally impose order on our messy democracy.

This type of thinking has filtered into mainstream conservative tech circles. J.D. Vance, Peter Thiel's protégé, has embraced aspects of this techno-authoritarianism. The appeal is straightforward: if democracy is inefficient and prone to capture by the "wrong" kinds of people, why not replace it with a hyper-rational machine-guided system? AGI becomes the ultimate justification for consolidating power in the hands of a technical elite who alone understand how to "align" this new god.

But the political left isn't immune to AGI's possibilities either. Center-left commentators like Ezra Klein increasingly frame AGI as a pathway to something resembling “fully automated luxury communism,” but packaged in a form acceptable to the center-right because it relies on tech companies instead of workers seizing the means of production. Under this narrative, AGI promises to make production so abundant that traditional capitalism becomes obsolete by its own logic. (Look for an upcoming post about this topic and Klein’s book, Abundance.)

In the authoritarian vision, the details of whether the technology actually works are irrelevant so long as the democratic welfare state is gone; in the abundance vision, the details are always forthcoming. In both cases, AGI functions as a convenient deus ex machina, promising to resolve intractable political problems through technological transcendence rather than the messy work of democratic deliberation and compromise. It allows people to project their utopian visions onto a blank technological slate, whether that's the ordered hierarchy of the neoreactionaries or the post-scarcity abundance of the progressive techno-optimists.

Wrapping up: an ecosystem of hype

These four categories of AGI believers aren't isolated, but form an interconnected ecosystem where motivations reinforce each other. Given how frequently some names above pop up in different contexts, many influential voices on AGI sit at the intersection of multiple categories, creating powerful feedback loops that amplify claims regardless of their validity.

Consider a junior engineer at OpenAI who is both financially dependent on AGI narratives for their career advancement (economic stake) while also socially embedded in San Francisco tech circles where AGI talk is the intellectual currency (social investment). If they're also drawn to Effective Altruism's worldview (spiritual yearning), they've hit a perfect trifecta of reinforcing influences that make talking them out of AGI as arriving soon nearly impossible. If they mostly hang out with other Effective Altruists who also work in AI, this deepens the entanglements above.

Even more potent are the interactions between categories. When a venture capitalist with billions at stake (economic) funds research that aligns with a politician's vision for techno-authoritarianism (political utility), while both move in the same elite social circles (social investment), we see how these incentives create an echo chamber divorced from technical reality. These elite tech social circles are *really small.* Wired has a piece out just yesterday on Eliezer Yudkowsky’s relationship with Peter Thiel, for example, while two AGI apostles mentioned above, Scott Alexander and Curtis Yarvin, go way back but have evidently recently had a falling out.

What's striking is not that people believe in AGI, but rather it's that when we filter out voices influenced by these four motivations, we find remarkably few credible experts still making bold AGI claims. Those without these incentives who work directly with AI systems tend to speak more cautiously about capabilities and timelines, focusing instead on present limitations.

This pattern suggests something crucial: the loudest AGI predictions come primarily from those with something to gain beyond mere technological progress. This doesn't automatically invalidate their claims, but it should sharpen our critical faculties when evaluating them.

In my opinion, the fundamental misunderstanding across these groups is a reductive view of intelligence itself. Human intelligence isn't just computational power plus data, but it involves embodied experience, cultural context, and neurosymbolic understanding that current AI systems fundamentally lack. A short story (which Altman claims ChatGPT can write well) isn't just pages of fiction, and a poem isn’t just verse; both are meaning-making shaped by lived human experience.

The most advanced AI systems still cannot reliably distinguish fact from fiction at scale, lack true comprehension of their outputs, and operate without genuine understanding of the physical world. These aren't incremental challenges to overcome but fundamental limitations of current approaches, and to my knowledge no real technical solution exists to any of these.

By understanding the constellation of incentives behind AGI claims, we can better evaluate which voices to trust and which predictions deserve our skepticism. More importantly, we can refocus attention on addressing real, present-day challenges posed by existing AI systems rather than being distracted by speculative futures that conveniently serve the interests of their proponents.

A critic might say here, who are you to question great men like Yoshua Bengio? For one, I’m not in fact critiquing the technical work, only commenting on his incentives. And second, luckily for me, Silicon Valley welcomes uncredentialed people, of which there are many in the AI field, so by the code of the tech elite I’m entitled to my own opinion here.

Brilliant, thank you for the analysis. Like you, I am hard-pressed to find voices making bold claims about AGI or even the future of current LLM approaches coming from people without a serious incentive like the ones you’ve outlined. I think it’s just good epistemic practice: explore the motivation prior to forecast. Also, interestingly, I find more prominent AI skeptics lacking an agenda, which makes me even more eager to listen.