Automation and the Dignity of Work

AI Will Put The Required Cover Sheet on the TPS Report

Last week, NPR Morning Edition host Steve Inskeep posted a transcript of his interview with former Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg and likely 2028 presidential candidate:

BUTTIGIEG: . . . Even though [artificial intelligence is] a hot topic and people are discussing it all the time, there's a lot of hype. I think even now we are under-reacting in a big way, politically and substantively, to what this is about to do to us as a country.

INSKEEP: What's the danger?

BUTTIGIEG: In addition to the dangers that do get talked about a lot, the apocalyptic scenarios, the economic implications are the ones that I think could be the most disruptive, the most quickly. We're talking about whole categories of jobs. Not in 30 or 40 years, but in three or four, half of the entry level jobs might not be there. And if that happens as quickly as it might happen, it'll be a bit like what I lived through as a kid in the industrial Midwest when trade [and] automation sucked away a lot of the auto jobs in the nineties—but ten times, maybe 100 times more disruptive because it's happening on a more widespread basis and it's happening more quickly.

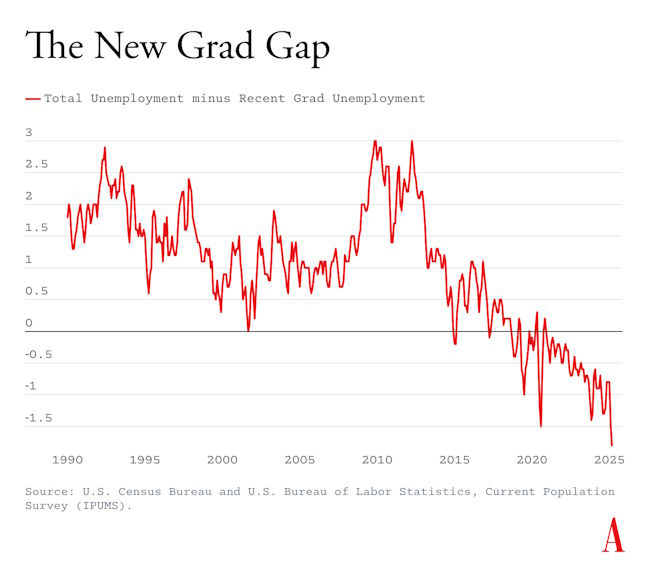

This is of a piece with a lot of the most reasonable commentary out there on AI: folks concerned with jobs and the impact of AI on the dire economic prospects of recent college graduates, with everyone from the Atlantic’s Derek Thompson to Steve Bannon1 getting on the AI job apocalypse bandwagon.

The analogy Buttigieg made to manufacturing decline is important for two reasons: it’s a political maneuver by Buttigieg, but it also is an inspiration to think about the risks of AI to employment in the context of what has gone wrong with American jobs over the past half-century.

On the former, Buttigieg’s comparison to employment in the Rust Belt is a deft political choice to court a certain voter base, and he’s not wrong on the substance of the comparison. Manufacturing jobs in the US both in real terms and as a percentage of jobs been in decline since a post-war peak in the mid-1950s, in large part due to productivity gains from automation.2 President Trump has long made attempting to reverse this trend a cornerstone of his campaigning; that is part of his justification for the tariffs now taking effect and part of his appeal to formerly solidly-blue Rust Belt voter blocs Buttigieg thinks he can win back.

On the latter, mainstream economists tend to treat jobs as interchangeable units of economic output, reducible to wages and productivity metrics, and most would say that yes, we’ve lost jobs due to automation, but these these losses have been offset by jobs created in the “service economy.” This technocratic perspective dismisses as mere nostalgia or culture war posturing the sentiment expressed by the political right that manufacturing jobs are more desirable because they're more “masculine.” Commentators on the American political left also roll their eyes at such talk, seeing it as retrograde gender politics or economic illiteracy. Anyway, someone driving an Uber generates GDP just like an autoworker bolting together a car, so what's the problem?

But we should also be asking, what kind of service jobs replaced manufacturing? And what does it mean for a society when the work that financially sustains most people's lives feels fundamentally different from the work that built their communities, particularly if that work serves an invisible, distant master who can easily replace you?

The “let’s make American jobs manly again” intuition, even if crudely expressed, points toward something economists miss entirely, and which is relevant to how we should think about the impact of AI on employment. What if the populist preference for manufacturing work over services work isn't really about gender norms, but about purpose, meaning, security, and feeling valuable to your community?

In the rest of this essay, I’ll outline how these questions can help us make sense of what sort of jobs are at risk because of AI, how other jobs may change for the worse, why we should be more worried about workers losing their jobs because of AI, not to AI, and what the most insidious threat to employment from AI really is.

1. Automating arbitrariness

The late anthropologist David Graeber offered a theory that made sense of the yearning to find meaning at work in the modern America’s corporate services economy: the phenomenon of "bullshit jobs."3

Graeber argued that a significant portion of modern employment consists of jobs that even the workers themselves recognize as pointless — roles that contribute nothing meaningful to their community or broader society and exist primarily to maintain existing power structures and economic hierarchies. These aren't just the obvious examples like corporate middle management, but vast categories of work that feel fundamentally arbitrary and hollow4 to those performing them: compliance officers enforcing esoteric regulations, schedulers managing the schedules of people who manage other people's schedules, consultants hired to advise consultants. The cult classic from the 1990s, Office Space, memorably captured the ennui of the bullshit job:

And so, as the bullshit jobs theory goes, we eliminated manufacturing jobs, but a non-negligible amount of regulations put into place over the last two generations essentially served as a jobs-creation program in the services economy. This is partially why, even with increased productivity in the manufacturing sector, we’ve never achieved what John Maynard Keynes predicted in the 1930s: that, by century's end, technology would enable workers in the United States to have a 15-hour work week.5

A year and a half ago, I did some focus groups about AI with Americans from a geographically diverse swath of the country, to see what they knew and how they felt, out of a hunch that elite coastal conversation was out of touch with the rest of the American population. One woman described how she uses an LLM tool to help her in her compliance job by speeding up the drudgery of completing forms. As she told her story, though, I noticed two things: first, she wasn’t any less busy than she had been, with more drudgery filling the void left by the LLM; and second, she realized she was ultimately training her replacement. Not only can an LLM help you fill out the cover sheet on your TPS report — it can probably do the whole thing, and it won’t have neglected to read the memo requiring cover sheets on all TPS reports that go out.

And that’s part of what I expect to happen with AI: bullshit jobs — particularly early career ones — are the ones that are at risk. Not only are they among the most automatable with LLMs, the error rate of an LLM doing something like a language-based compliance task or the first draft of a presentation deck is probably no worse than your average junior-level employee. Accounting will be trickier, given that there’s numbers connected to dollars involved, but having spent close to two years at Ernst and Young earlier in my career, I can tell you there’s a lot of bloat at large accounting firms, again particularly at the most junior grades, but also among partners.

As anyone who has worked at a big enough company to have internal IT systems knows, these things don’t usually work as they are promised — and that’s even before you take into account the erratic tendencies of LLMs. So what that will look like instead is more senior, experienced employees debugging the results they get from automation. Even if on net this amounts to less time spent on correcting errors than one would spend correcting the work of a more junior human being, the old fashioned way comes with the potentially rewarding social experience of teaching and mentoring an actual human being, not to mention career development for that human who would be a potentially valuable future senior employee. And because of enshittification being core to tech’s business model — particularly once businesses are locked in to using a product — it’s likely that quality will further decline over time rather than improve.6

Bullshit jobs also tend to be in a company’s cost centers — like compliance, tax, and trust and safety at tech companies7 — rather than its profit centers. Companies are always looking to cut costs from cost centers, and executives in charge of those departments often only have letting people go as a way of showing savings to the company when there’s downward pressure on costs — particularly when an increasingly permissive regulatory environment makes it difficult to show how their department otherwise saves the company money or mitigates risk. We are in such an environment now.8

I’ll come back to this at the end, but if you feel like you have a bullshit job in America, the economic news of the last week should also have you on high alert.

2. A hollowing out of ‘good’ jobs

Recently Brian Merchant shared letters he’s received from tech employees about AI in the workplace, and all of the stories are depressing. I recommend reading the whole piece, but here’s one salient quote:

Our department has now brought in copilot, and we are being encouraged to use it for writing and reviewing code. Obviously we are told that we need to review the AI outputs, but it is starting to kill my enjoyment for my work; I love the creative problem solving aspect to programming, and now the majority of that work is trying to be passed onto AI, with me as the reviewer of the AI's work. This isn't why I joined this career, and it may be why I leave it if it continues to get worse.

And this is the other half of what AI is doing to employment: it’s going to take jobs people enjoy, and turn them into bullshit jobs. This is not a novel observation; I’ve seen this pithy comment pop up near-weekly, for example:

OpenAI has defined “artificial general intelligence” as “highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work.” At the heart of the matter here is the question of what’s valuable economically, and more importantly, valuable to whom. Your dishes and laundry and bathroom being clean may be valuable to you, but their cleanliness isn’t valuable to shareholders. Art is not really valuable to shareholders either; “content,” however, is, and generative AI can now produce it for a minimal cost compared to a human’s art. This is why art and writing are being systematically devalued through corporate piracy and replaced by AI slop.

Beyond creativity, though I would bet that the aspects of any job that you have enjoyed were likely not the aspects that were the most economically valuable.

Large tech companies building LLM systems are angling for them to become the next “platforms” — as the web browser and search were in the original 1990s internet boom, followed by app stores and domain-specific monoliths (Amazon for retail, Airbnb for lodging, Uber for transportation, Microsoft for business, etc). OpenAI and their ilk want to mediate as much of your daily activity as possible, so they can have the data and so they can take a cut of any economic value for themselves as rents. As this works its way into the workplace — if by executive decree in your organization you must become “AI native” and you must use AI to schedule a meeting or take notes at that meeting or coordinate follow-ups with coworkers — I would expect such mandates to sap feelings of workplace belonging just as much, if not more than, the COVID lockdown remote work era did.

In short, if you like human moments in your workday, just know that they are likely not economically valuable and as such are at risk of being automated away.

3. Job loss “because of AI,” not “to AI”

Middle managers get a bad rap from both those above and those below them, but what a good middle manager does is solve the problems inherent to translating the strategic directives of larger organizations’ management into the daily work of a team and back again, while smoothing over friction points in team dynamics. A good middle manager knows this and derives enjoyment from the challenge, and in so doing is learning how to be a good future executive.

But these challenges are not in themselves economically valuable to a company any more than bad weather is economically valuable to a shipping company — they are just realities to be handled. So if you can dispense with messy humans and thus also dispense with their frictions, a good middle manager’s problem-solving ability is no longer of value either.9

Middle management may or may not be a bullshit job, but I’d expect the couple of years ahead to be very dire for experienced managers. The jobs market has been impressively sticky over the first months of the second Trump administration despite uncertainty surrounding tariffs, but as the jobs report from this past week showed, that may have been a mirage. As Josh Barro wrote Friday:

. . . [T]he labor market is frozen now but might soon unfreeze in a negative direction. . . . [F]irms are stuck: They lack a sufficiently positive business outlook to add workers, but they also don’t want to lay off workers, because of their “fresh” memories of how hard it was to staff back up after pandemic layoffs. Instead, they have been maintaining their staffing and accepting lower profit margins.

If the administration’s direction on tariffs holds, and costs thus rise further, firms may have little option other than to begin to lay off workers, as accepting those lower margins can’t hold indefinitely.

Yet because of political pressure from the administration to avoid bad news about markets and prices — the President did fire the BLS official responsible for the jobs report, after all — I would expect companies to use narratives blaming AI as their out. They will continue hiring fewer new grads — which doesn’t really make the news on a company-by-company basis since it’s hard to track — replace bullshit jobs in cost centers with technology, and eliminate middle managers, perhaps elevating some junior staff to take their place. This may even start with big tech companies themselves: even though all of them beat expectations on their most recent quarterly returns, between AI infrastructure investments and salaries, tech companies are still burning cash at unsustainable rates while limping along with money-losing business models for their AI products. Tech companies routinely reorganize — I went through half a dozen reorgs at least in my four years at Amazon — and an AI-powered reorg and middle manager layoff would not be out of the ordinary. But none of this means these jobs were lost to automation; automation will instead be the excuse.

Dignity Can’t Be Coded

Looking at the broader trajectory here, what I see is less a story about artificial intelligence displacing workers so much as large businesses using AI as convenient cover for the same structural dynamics that have been hollowing out the dignity of American workers for decades. The manufacturing jobs that once anchored communities — the supposedly "masculine" work that populist politicians on the right invoke — weren't valued because they required testicles. They were valued because they created things people needed and because they embedded workers in webs of mutual social dependence that made them respected in their communities and harder to replace.

AI's most insidious threat to labor thus isn't mass unemployment. Instead, AI will accelerate the transformation of services economy work into the kind of surveilled, deskilled, easily substitutable tasks that strip away everything that makes going to work feel worthwhile. The programmer whose creative problem-solving gets reduced to reviewing AI-generated code, the middle manager whose hard-won expertise in getting the most out of her team becomes irrelevant when there are fewer humans to manage — these aren't stories about AI taking jobs so much as technological degradation of these folks’ dignity. Putting cover sheets on TPS reports is degrading enough, but spending your days fixing AI’s errors on TPS reports will probably feel worse.

Feeling that you’re connected to something larger than a quarterly earnings report, that your labor should feel necessary rather than arbitrary, that you should be able to see the material consequences of what you do — all are yearnings for purpose and worth. The longing isn't for masculine work per se, but for work that feels real — work that would be missed if it disappeared, work that contributes to human flourishing rather than extraction and rent-seeking. I suspect those of us who want to feel valued at work are all going to end up yearning too. 10

Bannon’s view: "I don't think anyone is taking into consideration how administrative, managerial and tech jobs for people under 30 — entry-level jobs that are so important in your 20s — are going to be eviscerated.”

Buttigieg attributes auto jobs being sucked away in the nineties to “trade and automation.” Buttigieg is correct to list them both. The collapse of manufacturing jobs was not the consequence of automation alone; the pain automation created was intensified and cemented by economic and trade policy changes made through the Nixon and Reagan administrations. These policies privileged paper shuffling in big cities over assembly lines in factory towns, irreversibly transforming the U.S. into a service-based and consumption-based economy, allowing more wealth than ever to be siphoned off by an ever-smaller few in the process. And so, by the year 2000, the Rust Belt stood as a monument to this reordering: not victims of just of technological progress, but casualties of replacing the machinery of wealth creation with the machinery of wealth extraction.

This essay was later turned into a book length work that’s a good read.

There’s lots of ways to find meaning in your life: parenting, faith, etc. A bullshit job may be completely satisfactory to someone whose cup otherwise runneth over, particularly if they can leave work at work, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

I used to have one of these bullshit jobs, and Graeber’s theory resonated deeply with me when I first came across it. In 2010, I was fresh off the boat from Peace Corps, sleeping on my best friend’s sectional in his 450 sq ft studio apartment, unemployed, with about $300 to my name, six-figure law school debt, and reliant for more calories than I should have been on a clerical error at Five Guys that turned a $20 gift card into a near-unlimited spending account there for at least 3 months. I took a job the only job I was offered after months of searching: it paid $17.50 an hour, with no benefits, to work in the Compliance Department at a USAID contractor, Chemonics International.

This job turned into a few other similar USAID compliance jobs. The gist was this: there’s a bunch of federal regulations that dictate how federal money can and cannot be spent on foreign aid, usually meant to prevent fraud and self-dealing, and to further other U.S. policy objectives. You couldn’t use a USAID grant to purchase slot machines or weather modification equipment. If you bought a car for a program with government funds, you had to buy it in America and ship it to wherever. If you used government funds to fly, you had to fly on a U.S. airline, etc. I had to know and help interpret and apply all these rules.

My legal training helped me parse the regulations and give guidance, and the upshot was that a few times a year I got to spend a month or two in an exciting place like Zimbabwe or Kyrgyzstan or Pakistan. But spend enough time doing that work, and you realize that most of these regulations were the result of government by train wreck — that a policymaker reacted after the fact to a news story and instituted a new rule to prevent it from happening again. The proliferation of rules meant a proliferation of tyrannical bureaucrats on the government side who spent their days negotiating with their counterparts on the NGO side about minutiae that have little to no impact on, say, a famine prevention program or local economic growth program. When Graeber’s essay came out in 2013, it put a finger on a malaise I had long felt, and around a year later I had moved to a new career in tech policy.

And so, as Elon Musk fed USAID “into the wood chipper” early this year, my horror at the destruction of what was, dollar-for-dollar, an effective aspect of foreign policy for the U.S., saved lives around the world, and employed many of my friends, was spiked with a dose of recognition that there was a fair amount of bloat . Contracting jobs at USAID itself could have been good candidates for some measure of automation, if purpose-built and well-designed. My mentor at Chemonics told me that if you do something more than twice, you should have a process for it. If you have a process for something, that’s something that can be automated, which is why Chemonics invested a fortune in creating all sort of internal process maps and flow charts documenting how work gets done in order to get ISO 9001 certified, something more associated with manufacturing than with the delivery of foreign aid.

This is actually already coming to pass in the tech industry itself! Although coding is one of the LLM use cases that has been most frequently trumpeted by the tech industry as a success, as Gary Marcus explained a few weeks ago, a new study from benchmarking nonprofit METR looked into the productivity gains for coders using AI who had an average of 4.9 years of experience, and their use of “current AI tools actually slowed down task completion time by 19%.”

Luisa Jarovsky has also recently posted the following:

I haven't found a single peer-reviewed paper covering AI-powered productivity increase that also takes into consideration the additional work required to review, correct, and oversee AI outputs.

The "increased productivity" and "socially beneficial" claims have been at the core of major AI investments and government partnerships, and have been raised to justify legal exceptionalism (especially in fields such as copyright and data protection).

Yet, it's 2025, and there doesn't seem to be a single paper capable of objectively demonstrating what AI companies have been marketing over the past two and a half years (including the review/oversight time, which they conveniently ignore).

Trust and safety probably belongs in all three categories I’m discussing here, depending on the nature of the company where it sits. These are jobs already being nearly fully automated away at places like Meta, or with low-paid contract workers in places like Kenya reviewing outputs (as has been reported with OpenAI), or having what’s enjoyable about the jobs being sapped by some level of automation in between. Here I think it’s important to make clear that I don’t think these jobs are bullshit, and whether a job is a bullshit one is always in the eye of the holder of the job.

And given threats to higher education and the nonprofit sector — home to many bullshit jobs as well — from the current administration, these jobs are also at risk as well.

Customer service is much the same, which is why customer service chatbots have so quickly become the norm for many companies. If you work in sales, you might enjoy interacting with customers — but what happens to your job when your customers automate more of their procurement process? The human element of sales, to the extent it can be separated from the sale itself, is of no intrinsic value to a company.

If you made it this far and are interested in this topic, I also recommend Matt Stoller’s take over at BIG.

Automation has always resulted in a decline in human creativity and craftsmanship, going back to when weavers were replaced with textile factories. Marx described alienation from a worker's productive activities long ago. But that automation always took a physical form, and so our society stopped giving status to people with impressive physical skills (unless they can be used in sports). There really aren't many good, widespread jobs which require use of the hands, other than medicine. Everyone else sits at a computer.

But after being told to pursue a career of the mind, that is being devalued too! I don't think AI is going to replace that many workers, but the cultural trend to disparage knowledge work and try to force it to be automated is going to sap the self-worth of a bunch of people who used to feel pride in their work. At this point, what kind of work does anyone aspire to?