The AI Bubble and the Extinction of the Mallrat

How Americans will foot the bill for market speculation

Quick note: I didn’t send out an email about it, but if you missed it, be sure to check out my recent post on Meta’s AI companion policy over at After Babel! - CM

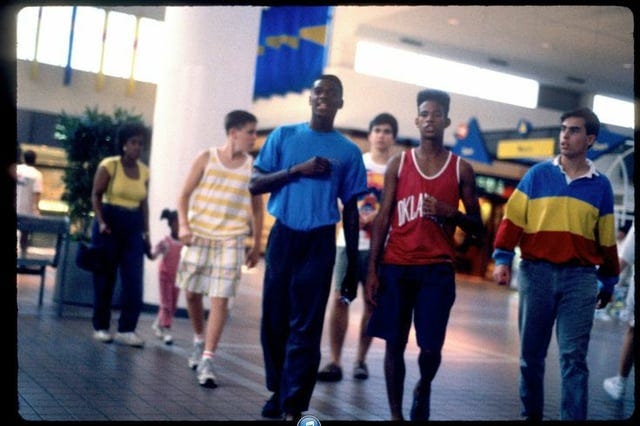

In Kevin Smith's 1995 film Mallrats, the characters spend an entire day wandering the mall, drifting from Spencer's to the comic book store to the food court with the casual confidence of creatures who are dominating their natural habitat.

Mallrats is not a very good movie and has aged poorly. Yet it did capture that the mall in the ‘90’s wasn’t just where people shopped, but where teens lived their social lives, learned about relationships, and figured out who they are. I was a teenager in the ‘90s, and I didn’t particularly care for the mall on its own terms, but I ended up there frequently anyway because it was one of a handful of places outside of school where you could dependably meet other teenagers. The ‘90’s mall was a genuine community space, a climate-controlled town square where different tribes of teenagers could come together and coexist.

That world seems impossibly distant now, not just chronologically but culturally. The mall as a social ecosystem has vanished, replaced by algorithms that sort teenagers into digital tribes instead. Yet the economic model that built those gathering spaces — a marriage of public subsidy and private speculation — has found new expression in today's data center boom.

Which brings me to why I'm writing about Mallrats in 2025. Over the last six weeks, the zeitgeist around artificial intelligence has begun to shift. Instead of tech journalists parroting industry hype about humanity's imminent encounter with superintelligence, even figures like Sam Altman and Eric Schmidt have started hedging their bets following disappointing releases like GPT-5. AI bubble discourse has moved to mainstream conversation. (More on the bubble here, here, and here.)

But the infrastructure investments behind AI show no signs of slowing. Communities across the country are competing to attract data centers with the same generous public subsidies that once lured shopping malls, convinced they're landing the next generation of economic development. The parallels run deeper than the financing structures. Just as mallrats once thrived in ecosystems subsidized by municipal debt, today's AI boom depends on public infrastructure investments and taxpayer-funded subsidies.

Today's data center building boom promises even less community benefit than the mall once did. Where malls at least provided social spaces and entry-level employment for teenagers, data centers offer communities almost nothing once construction is complete. These windowless monstrosities often employ fewer than fifty people, the overwhelming majority of whom are likely to be transferred in by a big company rather than hired locally. (The environmental issues on data centers are well-covered by others; I won’t discuss those here.)

And yet, communities across the country are competing to attract these facilities with increasingly generous incentive packages, convinced they're landing wealth and prosperity for the next generation. Rural counties in particular are offering public subsidies for data centers that work out to hundreds of thousands of dollars per job created, justified by projections of long-term economic development that echo the lofty promises made by mall developers decades before.

And herein lies the relevance of Mallrats: the communities that subsidized shopping malls were left holding the bag when the retail model collapsed, while the developers and anchor tenants extracted their profits and moved on.

When the AI bubble bursts, we can expect the same story to play out on an even larger scale — the richest companies in the history of the world will run away with their gains while the predominantly rural communities hosting data centers inherit decades of debt service and maintenance costs for obsolete infrastructure.

The Secrets of the Ghost Mall

The malls of the previous generation were massive public-private partnerships that reshaped the economic fabric of cities and towns and changed how American communities financed their own development. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, municipalities competed aggressively to attract these developments by offering property tax abatements, infrastructure improvements, and favorable financing arrangements. The promise was seductive: shopping centers would become economic engines, generating steady tax revenue while creating jobs and anchoring new housing developments.

But this created a perverse incentive. The more optimistic a community was, the more reason for developers to hype the potential of a development, and the more the economics of the deal would be stretched. Near-worthless open land on the margins of a city that generated no property tax revenue could be turned into a hub for the development of all the other near-worthless land around it, with each new dollar in property taxes from new subdivisions now available to backfill underfunded public services elsewhere in the community in addition to covering the cost of the subsidies for the mall developer as well as the cost of services to the newly built areas.

The economic assumptions underlying these deals now seem remarkably naive. Consumer spending would continue growing indefinitely. Big box stores and malls would remain the dominant retail format for decades. Anchor department stores — Sears, JCPenney, Macy's — would provide the stable foot traffic that kept smaller retailers viable. When I worked in the private sector, I negotiated similar deals, and it’s shocking how often municipal officials just take developers’ word for it when it comes to these types of projections. Based on these assumptions, communities issued municipal bonds to finance the roads, water systems, and electrical infrastructure these developments required, confident that property tax revenues would materialize from the new developments and more than cover the debt service on those bonds.

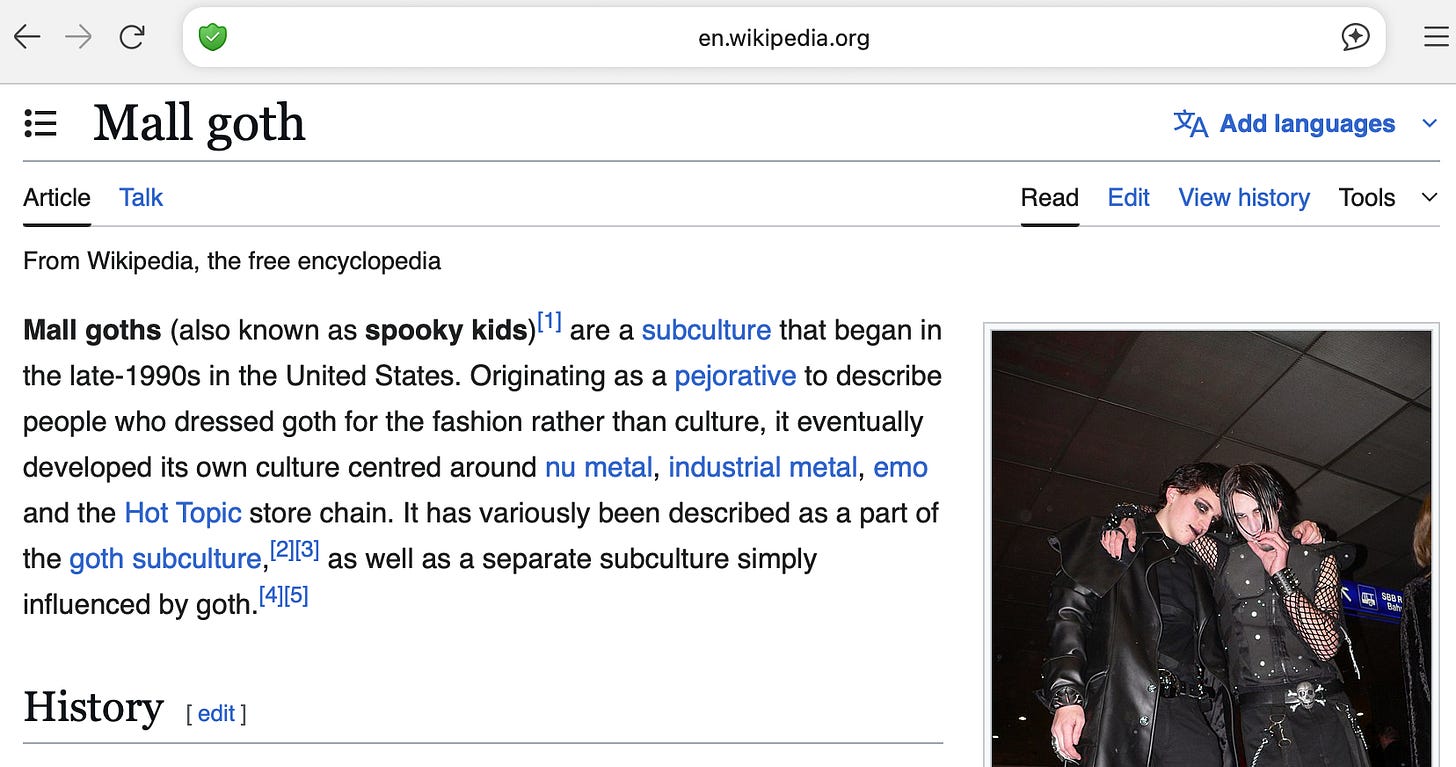

Thus, the teen goths shopping at Hot Topic were thriving in an ecosystem subsidized by municipal debt that assumed continuous growth and permanent relevance. The same public financing that made their social habitat possible also would later poison their communities from within, because the economics of mall retail could never support the infrastructure investments required to sustain it once the world outside the mall changed forever.

The world changed forever with the 2008 financial crisis and Amazon's simultaneous assault on brick-and-mortar retail. When consumer spending declined overall and Amazon offered a convenient alternative to mall shopping that also happened to allow the shopper to dodge sales tax, the carefully constructed mall ecosystem collapsed with stunning speed. Anchor tenants began closing stores, which triggered lease escape clauses that allowed smaller retailers to abandon their locations. Within a few years, the vibrant retail ecosystems that had anchored suburban life for a generation became empty shells.

One out of every six malls in America closed after 2013. When malls began to fail, the economic consequences were felt far beyond retail workers and store owners, and these consequences started not with job losses but with public debt. Municipalities that had granted decades-long tax abatements suddenly found themselves servicing infrastructure debt with no corresponding revenue stream. A community that had issued $50 million in bonds to support a mall development in 1995 would still be making debt payments in 2015, even if the mall had been abandoned. The roads, sewer systems, and electrical infrastructure remained, requiring ongoing maintenance, but the property tax revenues that were supposed to pay for that maintenance evaporated along with the retail tenants.

This revenue shortfall can create a death spiral: declining property values around abandoned malls reduce the overall tax base, forcing municipalities to either cut services or raise taxes on remaining residents. Either choice will make a community less attractive, encouraging further population loss and loss of tax revenue.

When Digital Infrastructure Becomes Digital Blight

It’s here that the lesson of the mall begins to be instructive for the AI building boom. If the market begins to believe that AI hype is just that and the bubble deflates, or if other macroeconomic trends depressing the non-tech economy begin to become more real to the market than tech valuations,1 effects will cascade throughout the economy.

(I’ve already written about AI and jobs here; I expect in a downturn for workers to lose their jobs because of AI rather than to AI, and for office work to generally get shittier. More positions that are salaried today will become gig-economy jobs, particularly at tech companies.)

In either case — and we may well end up with both a burst bubble and difficult macroeconomic headwinds — consumer demand will slacken, which will weaken business demand for things that need data center infrastructure; because of that weakening, planned new tech infrastructure investments will likely no longer pencil out as worth the cost (which may happen sooner than later since AI doesn’t seem to be making anyone more money than it costs to build, and seems like it won’t anytime soon). Inevitably, some data centers will close or even never open.

Building a data center is expensive. The infrastructure investments required to support data centers typically dwarf those needed for retail development, where the greatest expense is usually building a parking garage (which is always more expensive than it should be). These data center facilities consume as much electricity as small cities, requiring significant upgrades to local power grids. They need specialized telecommunications connections and cooling infrastructure capable of handling enormous heat loads. Public subsidies exist to abate all of these expenses.

But due to the scale of these costs, the fiscal math on a public subsidy for a data center that fails will be predictably brutal by comparison to a mall.

But what about repurposing an abandoned facility to prevent blight and keep up property tax revenue? Here, malls also offer another lesson. The specialized nature of suburban and exurban mall infrastructure makes recovery difficult when a mall fails. Big box retail stores that cluster around malls like Home Depot or Bed Bath and Beyond are custom-built for specific tenants, and it’s rare that another national retailer will spend the money to retrofit a space for their use. (Barnes and Noble, say, typically will not try to retrofit and move into a former Toys ‘R’ Us space, for example.) A former department store can’t easily be converted into a manufacturing facility or a community college campus. Sometimes, in the South, you’ll see a church or maybe a branch of the DMV that has moved into an abandoned mall space. These buildings rarely have windows, which limits their potential usefulness; a casino is just about the only other enterprise apart from big retail that would consider a windowless structure as an architectural asset.

By comparison, repurposing a data center is even more difficult than repurposing an abandoned mall; data centers are meant to hold racks and servers, feed them electricity, and keep them cool. They are not built for humans, but only to facilitate humans servicing the technology that lives there. And the chips used for AI are not necessarily useful for other technology purposes, so a facility filled with state-of-the-art GPUs from NVIDIA may be worthless for other uses.

To illustrate: a farming community that grants a twenty-year tax abatement for a data center that shutters after five years will lose fifteen years of expected revenue on the property, while incurring the costs to maintain expensive infrastructure while servicing the debt that financed it for that period.

The roads, power systems, and telecommunications networks built to serve the facility will remain and require maintenance even if a facility is abandoned; police will have to patrol the facility and fire departments will have to save it from burning down. Because infrastructure is often paid for with bonds, it can’t be just abandoned to be reclaimed by the prairie or forest.

Low demand in the industry and the specialization of the building make it impossible to find a different occupant. The blight from the abandoned building will bring down surrounding property values, hitting tax revenue again.

If it’s in a populated area, that decline in property values could result in the same fiscal death spiral I mentioned above. I think every American is instinctively aware that a data center is a worse neighbor than a Walmart or a truck stop — as my hometown of Memphis has learned — so it would surprise me to learn of any plans to build new subdivisions around data centers the way it happened with malls, which reduces the death spiral risk. A silver lining, maybe.

Socialized Loss, Privatized Profit

Destiny USA, a shopping mall in Syracuse and the biggest mall in New York, has problems. It was appraised at just over $200 million in value, and yet the debt on it is more than half a billion dollars, including more than $200 million in public bonds. The owner has defaulted. "Someone's going to lose money,” the county comptroller said back in 2021. “I don't know who it's going to be. Whether it's the commercial lender, bondholders or the current property owners, there are multiple ways this could go." Thankfully, bondholders will get paid first before other lenders, but it’s possible that what gets repaid is a fraction of the amount financed. It’s now 2025, and this is still unresolved.

Destiny USA isn’t a dead mall, though it is a quarter empty. Were it completely vacant, the troubles would be worse. By the time malls fail and big box retailers abandon locations, the developers who had profited from the initial construction will have been long gone, having years ago extracted their gains and moved on to new projects. The companies that had operated the anchor stores that closed could write off their losses from the store as tax deductions. The only people left to pay the bills are local taxpayers, with their communities left worse off than before the ‘development.’

This is a final lesson for the AI building boom. Just as communities that had competed for and subsidized malls were left with debt while the developers and retail chains kept their profits and got a tax write off, something similar may now play out with tech companies.

Already, the computer hardware in a data center is a depreciable asset2 for tax purposes, which creates a tax advantage for large companies. But tech companies that close a data center can take advantage of the same write-offs that anchor tenants in malls used: net operating losses allow companies to use current year losses to offset future profits, effectively turning failed investments into tax shields. This means that a company's over-investment in AI infrastructure that proves economically unviable becomes a valuable tax asset that can shelter profits from future business ventures for years or even decades.

Thus the infrastructure overbuild is a gamble the companies are willing to make, because it’s win-win. If a bubble doesn’t burst, it was a worthwhile bet. If it bursts, someone else picks up a big part of the tab. This represents a profound form of intergenerational theft, though it's rarely described in such stark terms. The same way that pollution externalizes costs that future generations will have to pay for one way or another, speculative infrastructure development externalizes fiscal costs to future taxpayers. The benefits flow to current political leaders who can claim credit for landing major projects, while the risks accumulate for their successors who will inherit the debt service and maintenance obligations.

Perhaps the best repurposing an abandoned mall can now find is as a clear message to today’s local leaders: if you care about your community’s future, don’t take the data center deal.

Just as the mall was the victim of a unique moment in history — when a global recession happened just as Amazon’s e-commerce business began to mature — AI will not be immune to the forces of history either. As of August 2025, big tech stocks account for roughly a third of market capital in the S&P 500, and those companies have all bet big on AI. But as September begins, President Trump, Speaker Johnson, and the rest of Congress are facing a showdown over a potential federal government shutdown. Trump’s tariff policies — while currently in dispute in court — along with his administration’s efforts to make unilateral cuts to past budgets passed by Congress as well as firing nonpartisan officials who manage the government’s economic statistics are all remaking the global economy. It seems likely that tech stocks have been propping up the market — AI spending outstripped consumer spending this year, even as MIT reported that 95% of private sector AI pilots have failed.

The depreciation deduction amounts to a government subsidy for data center construction that rarely gets discussed in policy debates about AI infrastructure. (This is in addition to any property tax or sales tax abatements the company may have negotiated.)

The mechanics of depreciation of property like computer chips — most of the cost of a data center — can get more favorable through accelerated depreciation methods. Data centers depreciate especially quickly, too: a facility opened in 2015 has probably had everything in it replaced three times already. For rapidly growing companies, these deductions compound as they layer new equipment purchases on top of existing depreciation schedules.

So, depreciation is an ongoing benefit while the data center is open, but if the company closes the data center, it can write off its costs as a net operating loss, which can be carried forward to unprofitable years.

this is a really, really great read.

also, this: "The same way that pollution externalizes costs that future generations will have to pay for one way or another, speculative infrastructure development externalizes fiscal costs to future taxpayers."